A Trip to Spain – The Way of St James

Stooping to scoop up a handful of snow from a wayside drift, with the temperature pushing 30 C, I confess that I wondered what had got me here, dragging my bike over the pass of Valcarlos, used by the Romans, by the Emperor Charlemagne's men, by Napoleon, by Wellington's army, and by countless others as they laboured over the Pyrenees, the mountain barrier separating France from that piece of Africa tacked on to Europe which is Spain.

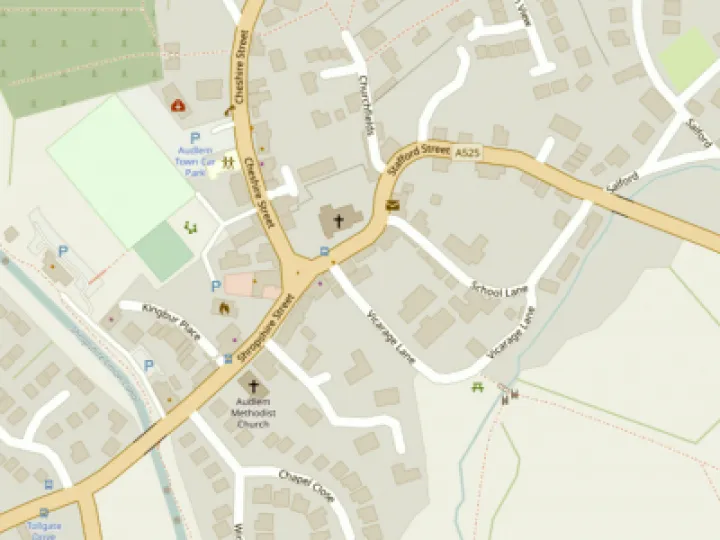

It started with that figure in the first window on the right as you enter Audlem parish church – top row, second from the left. "Sanctus Jacobus Major" it says (Saint James the Great, the church's patron saint). He's one of the twins whose mother wanted them to sit on the right hand of Jesus – Boanerges, the Thunderer. Of 18,000 parish churches, only about 400 have this dedication, so it's special. He's dressed for hiking, medieval style: long cloak, strong stick with a water gourd, a satchel at his waist, and a broad brimmed hat with a scallop shell badge. I had seen these scallop shells before, on the front of houses in Le Puy, in Central France, among other places, and I had read the great poem Sir Walter Raleigh wrote the night before his execution:

"Give me my scallop shell of quiet,

My staff of faith to walk upon,

My scrip of joy, immortal diet,

My bottle of salvation:

My gown of glory, hope's true gage,

And thus I'll take my pilgrimage."

So I did some more reading: books such as Edwin Mullins's "The Pilgrimage to Santiago" (especially good on architecture and art), "Pilgrim's Road" by Bettina Selby, an intrepid cyclist whose route started at Vezelay, and Rob Neillands's account of his cycle journey from Le Puy. His book introduced me to the Confraternity of St James, based in London and dedicated to supporting anyone who is interested in the pilgrimage to Santiago or in any aspect of the pilgrim route, with its indefatigable secretary, Marion Marples. (www.csj.org.uk)

As I read on, even visiting Europe's first tourist guide, the Codex Calixtinus, written about the way by Aymery Picaud, a French priest, in 1140-1150, I began to realise that for well over 1000 years something like 100,000 people a year, from all over Europe, had come together at four great gathering places in France (Paris, Vezelay, Le Puy, and Arles) and then marched westwards, to a place near, for them, the end of the earth, Finisterre – AND THEY WERE STILL DOING IT!

Why? Basically, in ages of faith, they wanted to get closer to a man who had walked beside Jesus Christ. The story starts with the apostles, spreading out to preach the gospel. It is said that James's "territory" was Spain, and even that he appointed a bishop in Astorga. He eventually returned to the Holy Land, and in AD 44 was executed by order of Herod Agrippa. However, his followers took his body back to Spain, landing at Padron, on the north west coast, and they buried his body some way inland. Many years later, in about AD 813, a hermit saw stars over a particular coppice, investigated, found a buried body, and reported it to his superiors. They readily came to the conclusion that it was the body of St James, the Pope supported the conclusion, and people started to visit the site, so that buildings developed there. Now this was all very convenient. At that time the Holy Land was inaccessible to pilgrims because Islam had taken over – but in northern Spain, the Muslims who had invaded from North Africa and ruled Spain for centuries were being pushed southwards. In one of the ensuing battles, at Clavijo, it was said that St James was seen, riding a white horse and swinging a sabre with the best of them, becoming "Santiago Matamoros" (St James the Moorslayer), and that settled it. He became Spain's patron saint, and a visit to his tomb became very desirable. In this different age, we are left to believe as much as we wish – but I was hooked. A European, steeped in its history and culture I would travel the way, accompanied by the ghosts of millions who had gone before!

Click on the images below to enlarge them:

How? From the Pyrenees to Santiago it is about as far as the distance from Dover to Aberdeen (c 600 miles), and from the gathering places much further – three months, walking from Le Puy, for example. Cycling across Spain was manageable for me – say three weeks. Look at the distribution of St James the Great churches in England and you see that many of them cluster along the Fosse Way, that great Roman route from York to the west country. From ports such as Weymouth and round to Bristol the early pilgrims would sail on the wine boats to Bordeaux and beyond. I would take the ferry from Portsmouth. So I did a little training, and organised my bike with two panniers and a front bag, and a small rucksack containing camera gear on the carrier. In the panniers were wet gear and dry gear, three sets of clothes (one to wear, one to wash, and one drying), toileting stuff and simple medicines (starter, stopper, plasters and the like). In the front bag were passport and papers, and an entertainment centre (Walkman for cassettes, watercolours and sketchbook). Two tablespoonsful of common-sense, and trust in the Lord.

Train to Portsmouth, P&O 72 hours to Bilbao, and I was on my way. I pedalled up river from the port of Santurzi and in the city a kind gentleman spotted the cockleshell on a bootlace round my neck and helped me book a coach trip back into France so that I could pick up El Camino Frances (The Road of the French) and start properly by going through St Jean Pied de Port (St John at the Foot of the Pass). There Madame Debril, from her home on the ramparts of the old town, saw me ride along the valley and was ready to stamp my pilgrim passport to mark my official beginning. In the middle ages these were safe conduct papers through the various kingdoms along The Way, and also exempted pilgrims from customs dues. Nowadays one gets them from the CSJ and has them stamped at stopping places as one travels, ready to have them inspected at journey's end.

Here I was then, approaching the summit of the pass, having pedalled and walked all day and ready (Oh, so ready!) to stop the night at the monastery of Roncesvalles, set up a thousand years ago to give support to pilgrims crossing the mountains, by the great Benedictine mother house of Cluny. I was checked into the dormitory by the guest master (a brother wearing a grey knitted cardigan and carpet slippers), and met two Dutch chaps, cousins who had cycled from Holland. Once we had got our beds ready and had freshened up, we went together to the Pilgrim Mass at 8-00 pm. I am not a Roman Catholic, just ordinary C of E, but it seemed right to follow the Mass and be blessed for the rest of the journey. Then we went for a good dinner together at a nearby bar, and shared a bottle of excellent Rioja – the first of many such companionable meals.

In the fresh of the morning we got our bikes organised and whizzed down the hairpins towards Pamplona, the first big town – they left me far behind! Think of Pamplona, think of bulls running through the streets, and the bull ring with its statue bust of Ernest Hemingway under the shade trees outside. You are down to about 800 metres above sea level now, and the way averages this for a long way, running westwards south of the Picos de Europa. But Spain is the third most mountainous country in Europe, and the way is corrugated by ridges – very testing to start with, and getting worse before they get better! Settlements, as you learned in school Geography, grow up at river crossings such as Puente la Reina, so in the evening you happily freewheel towards a bed for the night, but every morning starts with a climb! There are wonderful sights, like the Templar church of Eunate, and a wonderful solitude – big country, small population – but automatic companionship among the pilgrims speaking many languages and great support and kindness from the Spanish people, who still take these things seriously. My good fortune was to meet a German couple, Walter and Barbara, who, each year for five years, had spent a part of their holidays cycling from their home near Cologne.This year they would complete their journey. Our paths crossed early and re-crossed often, each meal together was a joy, and they have become like brother and sister to me.

Burgos is impressive, a big city with an ancient walled town and a ruined castle. Here Christopher Columbus reported back to the king and queen after his journeys to America, and in the beautiful Monasterio de las Huelgas are the stone coffins, carved and painted, of many long dead royals. I took a day's rest there, and when I walked up to the castle ruins thought I was alone, looking down across the city spread below, until the haunting sound of a gypsy song sailed out, sung by an old man to the clouds and birds, as he thought.

Pilgrims return with two particular physical memories of the Camino: the mountains – and the Meseta. it starts just beyond Burgos and is a wide, flat, treeless plateau of grain growing land. In England we are used to having a settlement every eight miles or so, with a church tower to mark it. On the meseta you can go for twenty miles and never see a soul – and it is hot! I came up with a Brazilian there, wearing one boot and one trainer as he walked The Way. He was wearing the ones which were comfortable, he told me. Somewhere along this stretch I first met Isidro, a marathon man, who was running from his home town of Logrono to Santiago (to publicise Marques de Caceres wine!). He had a support car with a female physio to see to his legs and feet every evening, and a male minder to drive and keep him supplied with drinks during the day (7-8 litres) and mounds of pasta at mealtimes. My cycle computer said he padded along at a steady 10 mph. I asked him how he kept going. He simply tapped his forehead "It is in the mind".

You leave the meseta behind at Leon, city of the Legions, with its black and white storks nesting on every pylon and Roman column, and by Astorga you can see some real mountains ahead and see the vegetation changing as you climb. The British Confraternity runs a hostel for pilgrims fifteen miles or so on, in what was a tiny hamlet (only 35 permanent residents) called Rabanal del Camino. People are given a dormitory bed, showers and washing facilities, and a continental breakfast. There is no charge, but donations are welcome. (Later I was to do two spells as a warden there – but that is another story).

Above Rabanal, at almost the highest point on the Way, 1514 metres (higher than Ben Nevis) is Cruz de Fer, an iron cross on a tall pole planted in an enormous cairn. I learned it is a tradition for pilgrims to carry a small stone from home, as a symbol of their prayers for those they love, and to leave it on the cairn. (It was here that I learned from Walter a new use for those long deep pockets at the rear of panniers. They are exactly the right size for a bottle of wine!) Take care on the steep descent to Ponferrada, with its iron bridge and fairy-tale castle. Cyclist have come off and killed themselves.

A couple of days later, beyond the pretty town of Villareal, full of cherry blossom and market gardening, you are climbing again – but don't despair. If you have had your pilgrim passport stamped, even if you are so bad you have to give up at this point or beyond, the Cathedral authorities will still issue you with a certificate of completion, a Compostela, as they reckon you have earned it if you get so far. It will take you all day to climb to the pass of Pedrafita, and beyond, up again, to O Cebreiro. It was 30 degrees and more when I got to the bar at the pass, and I decided I had earned a beer. An older lady interrupted her knitting of white bootees for a new grandchild to open a chilled bottle, and as I drank asked me where I would stay the night. When I told her, she suggested I should go on, over the mountain and to the next town, as it would be cold. I could not believe it, and I was tired, so I stopped at O Cebreiro as planned. She was right though. Next morning there was six inches of snow on the ground.

In the same village, a strange place with some low walled, egg shaped dwellings with thatched roofs, part of an ancient tradition, was Isidro and his team, who happily greeted me. At dinner that night, I was invited to share the table of an Englishman, who was touring with his wife and her friend, in their new Volvo estate. He kept asking me where I would stop the next night, how far was it, had I booked ahead, how many miles a day did I manage, when would I arrive in Santiago – and I could give him no answers. I realised El Camino had taken me over and that I was outside the pressures and harassing timetables of our modern world. God and the strength (or weakness) of my body would give the answers, and I would accept what came.

And so El Camino drew me to its end, gradually falling down towards sea level, leaving the mountains' snow behind, finding it replaced by Galicia's west winds and frequent rain. Then the fruit blossom began to appear, and Friesian cows in fields with hedges, and I was nearing journey's end.

Through the industrial suburbs, across the motorway, into the city itself, and finally the narrow streets of the old town. More pilgrims now, singly or in groups, all heading for the Plaza d'Obradoiro (a square the size of a football pitch) and the Cathedral. Up the steps. Fingers into the hand smoothed spaces in the column at the entrance, from which Christ smiles gently down. Down the aisle, crammed with bus-borne tourists, and to the high altar, with its golden bust of St James, Santiago. Conveniently, steps take you up behind him so that you can lean forward and give him a hug. You have completed your pilgrimage!

However, there is one more task. You need to check in at the Pilgrim Office in an adjoining street. There, a priest (for years Father Jaime), will ask you questions to probe the authenticity of your pilgrimage. Your name? Where are your from? (At midday Mass next day you may hear yourself mentioned.) Have you got a "credencial" with its stamps from along the way? And, finally, what was your motivation? When I set out, I would have answered historical, cultural, sporting, aesthetic – but now I could truthfully answer yes, when he gently suggested religious? Spiritual? It had opened a new chapter of my life, as it could for you.

And so I was issued with my first "Compostela". (Later I was to earn two more, but those are another story). I had it photocopied, because if you present it to an official at the five star Parador, Hostal de Los Reyes Catholicos, next door to the Cathedral, you are entitled to three meals a day for three days (you enter through the garage and eat in the servants' quarters, I must add, though it's pretty good nevertheless). The hotel was built as a hostel for pilgrims, centuries ago, and they carry on the tradition of hospitality.

Not long afterwards, it was time to head for home. I had not seen Barbara and Walter for three or four days, as they had had a couple of days rest, and I was sorry, very sorry, to miss them. I went to the Pilgrim Office to see if they had checked in, but no. Downcast, I went to the Cathedral for one last time before going to the bus station to catch my coach to the ferry port. A prayer of thanks, and it was time to go. Then, as I walked down the steps towards the great square, there, from the far side two familiar figures walked towards me. All was well.

The Confraternity of St James (www.csj.org.uk) is the best source of information on the pilgrimage in Britain, and we serve the USA also. Many European countries have their own national associations. Every year a CSJ guide to accommodation, cycle repair etc is published.

The best guide to the route in English is "The Way of St James – The Pilgrimage Route to Santiago de Compostela" published by Roger Lascelles, Brentford, Middlesex, ISBN 1 872815 26 X. It has an excellent introduction, giving details of various national associations, and the maps are based on those drawn by the late Dr Elias Valina Sampedro, the Spanish priest and university teacher who first formalised, established, and way marked the route in modern times. The little blobs of yellow paint along the way are the work of volunteers whom he first organised. Travellers along El Camino are greatly in his debt.

If you read French, and are interested in history, then try "Priez pour nous á Compostelle" by Pierre BARRET and Jean-Noel GURGAND (Hachette, Paris 1978) ISBN 2-253-02399-X

The two authors walked from Vezelay to Compostella, and tell their story – but also weave into the tale extracts from the accounts left to us from French, English, German and Italian pilgrims from 1380, 1417, 1477, 1488, 1495, 1496, 1512, 1670, 1726, and 1748.

A double CD "The Pilgrimage to Santiago" performed by the New London Consort under Philip Pickett will introduce you to the ancient music of El Camino, through Navarre & Castile, Leon & Galicia. (L'Oiseau-Lyre 433 148-2)

Copyright: Howard W. Hilton, March 2006

This article is from our news archive. As a result pictures or videos originally associated with it may have been removed and some of the content may no longer be accurate or relevant.

Get In Touch

AudlemOnline is powered by our active community.

Please send us your news and views using the button below:

Email: editor@audlem.org