History Short No 40

Audlem and District History Society

General editor – Jeremy Nicholls

I came across cryptic or cipher runes on a trip to Orkney some years ago. I had read a bit about standard runes, their semi-magical meanings, and the various versions of the characters themselves.

But in the Orkneys the Vikings happened by in the early Middle Ages, and following their general principles of raping and pillaging, they defaced some perfectly good standing stones and stone age buildings which had been happily sitting there relatively undisturbed for several thousand years.

The standard runic alphabet (and it is an alphabet, not pictograms or hieroglyphs) is called the futharc, based on the first six characters of the alphabet. There are then two more rows of characters. There are many versions of this alphabet – this one is called the Elder Futharc Runes.

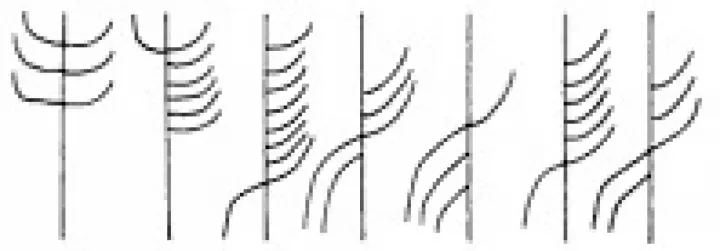

But the cryptic runes, as well as sometimes being backwards or even upside down, are based on a numeric code, where the branches to the left of the stem represent which row of characters, and the branches to the right represent the character in the row.

.

These runes are supposed to represent"ek vitki", whatever that may mean.

Now when you think about it, the idea of representing a given letter by what is really a grid reference within a chart is pretty clever and fundamental. If you know the chart (which is just like saying your ABC) you can work out which letter each individual rune represents.

So, was there a Viking version of Bletchley Park on the Orkneys in the early Middle Ages?

The necessity to represent letters this way did not really arise again until computers – codes like Morse Code and the Dancing Men in the Sherlock Holmes story were only ways of representing individual letters by a code specifically corresponding to that letter.

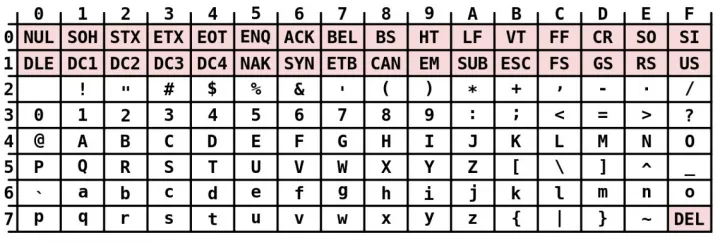

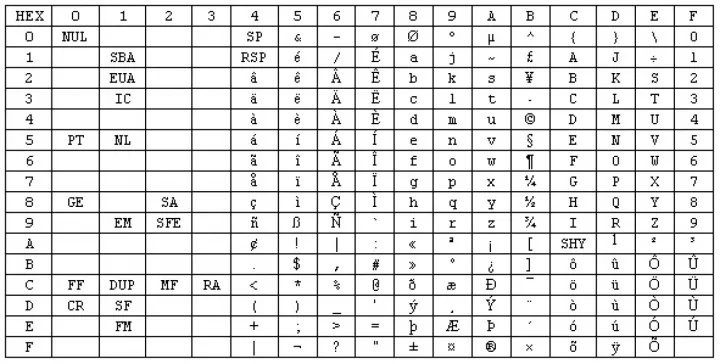

But then came computers at the end of WW2 and the specification of EBCDIC (Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code) and ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange), the two standard, but annoyingly different, ways of representing English letters by a numeric code by listing the letters in a grid and using row/column numbers to define the letter.

ASCII code chart

EBCDIC code chart

So, the Viking equivalent of Alan Turing sitting on his windy Orkney Island around 1000AD was a whisker away from the creation of a computer, needing only the invention of electricity, valves, transistors etc to make the thing a practical proposition.

Postscript

And, just so you know, the codes for "ek vitki", in lower case and including the space, are:

ASCII – 65-74-20-76-69-74-6B-69

EBCDIC – 85-92-40-A5-89-A3-92-89

{

}

John Tilling

Get In Touch

AudlemOnline is powered by our active community.

Please send us your news and views using the button below:

Email: editor@audlem.org