Editors note:- due to the size, we have split this overall report into 2 – Part 1 today (Saturday) and part 2 tomorrow (Sunday)

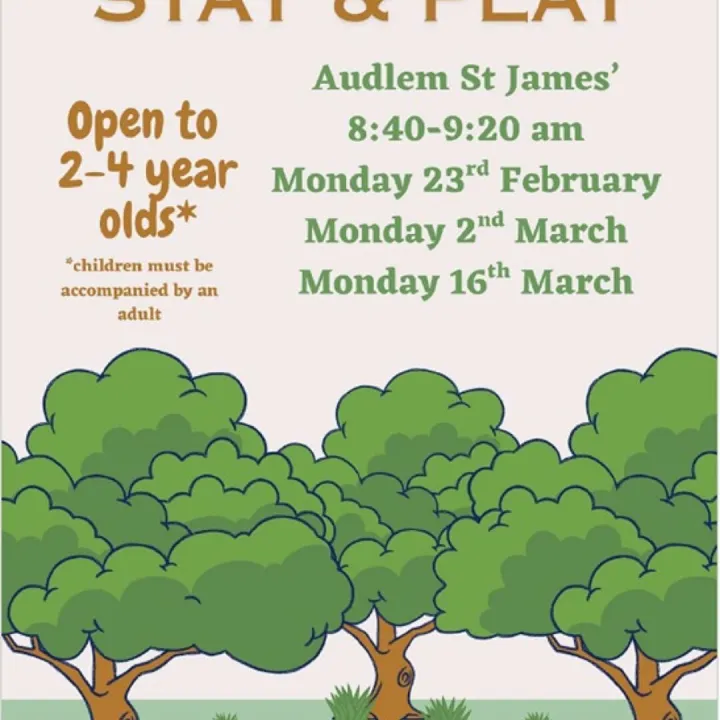

"Sail south until the butter melts!" An Atlantic adventure.

Bob Fousert with apologies to real Sailors.

Phase 3 (Part 1) – Las Palmas to St Lucia/Trinidad (3200 NM – 3680 Miles)

One of the criteria for joining an ARC (Atlantic Rally Cruise) is that crew members must have undertaken at least 500 nm (nautical miles) of prior 'blue water' sailing. In that respect our 1900+ nm covered in the first two phases from Hull to Las Palmas more than qualified our crew.

Arriving back in Las Palmas four days before the Sunday 9th January departure we were kept busy with safety equipment inspections by the organisers, briefings and seminars for skippers and crew, passport and boat documentation inspections and undertaking yet another PCR test to enable us to disembark at St Lucia.

In addition we needed to ensure we had enough fresh food and rations for at least four weeks, plus additional fuel and water (160ltrs of each) over and above what the tanks on the boat already carried.

As such, the pontoons on which the ARC boats were moored were more akin to a market place than a marina. By the time we had finished loading everything, the boat was lying a lot deeper in the water than usual but on an even keel as the weight had been well distributed.

The flotilla of 47 yachts from 23 different countries was handicapped and divided into the out and out racers, usually 50 – 70 ft boats with six to eight crew, multi hulled boats (catamarans) and the remainder whose primary aim was generally to achieve the crossing in the time allotted. It was for each skipper to decide which route to take across the Atlantic.

Freeway as the second oldest, smallest (35ft) and heaviest (ton/metre) yacht in the fleet was allotted the biggest handicap.

There is a 'yachty' saying that in order to get the maximum benefit from the easterly trade winds that cross the Atlantic, you "Sail south until the butter melts". At which point, somewhere in the area of Cape Verdi, you should benefit from those winds.

the start!

While the racers crossed the start line at 12.30, a mile off the coast of Las Palmas, we jockeyed forposition in preparation for our start at 13.00. In lovely sunshine, a strong wind and a big sea swell, instead of sailing due south we sailed due East for 10 miles in order to be able to tack and clear the south of the island in a single run. (Nothing is ever straight forward when sailing. You quite often have to go in the wrong direction first.)

From the start and once clear of Las Palmas, it was our intention to sail south but for no longer than necessary and try to turn west as soon as the trade winds were in evidence. Meanwhile many of the racers immediately turned west, thereby taking a more northerly route than most of the fleet. This meant that within a few days the fleet was scattered over hundreds of miles of sea.

Atlantic crossings are as challenging to the yachts as they are to the crews who sail them. Within two hours of the start one of the leading yachts had to return to the marina because of problems with the security of the rigging to its mast. They eventually rejoined the race 24 hours later. More drastic events were to come!

Phil made the decision that we would do 4 hour watches wearing life jackets and attached by safety harness, but only from 20.00 to 08.00 after which, during daylight hours it was more casual and down to whoever was up in the cockpit. This system worked very well though the timings were put back by one hour every time we moved from one time zone to another (Trinidad is four hours behind the UK).

10.01.22 13.00

Having completed our first 24 hours at sea we were over 100 nm south of Las Palmas, 120 nm off the coast of Africa and had covered a very respectable total of 138 nm. Over the AIS we received numerous coast guard radio calls to be on the lookout for migrant boats trying to make the trip north to Las Palmas as this is one of the major routes from Africa into southern Europe. Though we did not see any migrant boats we were once again accompanied by a pod of dolphins and also spotted a lonely turtle.

However, this good progress did not last long as the next day the wind had dropped to just 4 knots so we had to resort to using the engine in order to make any headway. In late afternoon we were followed by a very large pod of dolphins who kept us entertained for at least 40 minutes, when about eight of them came right up to the back of the boat nudging the rudder with their noses – a fantastic close up sight. That night, near to midnight there was a lot of luminous sea activity to our stern with a trail of lights flashing on and off in the water and what looked like large bursts of light which we believe could have come from jelly fish. This spectacle repeated itself night after night.

A near miss

After four days at sea we finally had company in the shape of two large liquid gas tankers that were also heading south. Whilst one passed us a couple of miles away on the port side the second only changed course at the last minute and was just 100 metres ahead of us when it finally passed from the starboard side – a bit too close for comfort! Whilst we were somewhat disappointed at our lack of progress because of slight winds, we did feel some sympathy for the two yachts still stuck in Las Palmas awaiting spare parts and a further yacht crew who were waiting for their skipper to arrive, who was delayed because of Covid.

Friday 14.01.22

A fabulous morning sunrise and a day when we had probably the most spectacular sighting of our trip. A pod of more than 50 dolphins raced towards our boat jumping and diving in the sunlit ocean, and there was me with no camera to record it as my phone was switched off down below deck. Even now, thinking of it, I am so disappointed that I couldn't record the event. They clearly thought that Freeway was a prime target for some fun and games and stayed with us for a good half hour or more.

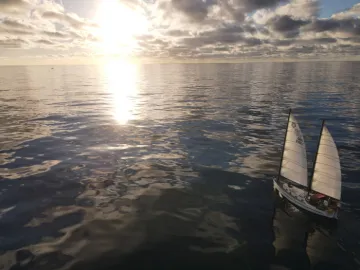

The following day we were once again becalmed and had to resort to our engine to make some progress across a sea that looked like a sheet of blue glass. Late that afternoon, at around sunset, we were very pleased to catch up with a yacht called Woolamai, which is German registered but was skippered by an Australian with his wife and her friend as crew.

Also being becalmed, they had spent their day just swimming and fishing, having caught a large, three foot tuna fish. Seeing another human being after five days was a real morale booster and we stopped with them for about an hour sharing some cans of beer from Phil's brewery before moving on. They stayed in touch with us via satellite phone for the rest of the crossing.

Because of the conditions which affected most yachts in the fleet, quite a number of boats that had been using fuel to steam south diverted to Cape Verdi to refuel and take on extra water. After some consideration we decided not to do the same as we worked out that it would be a 150 nm trip just to get there and by the time we made up the distance we would probably have used as much Freeway in a becalmed sea (aerial view taken by the Wollamai skipper) fuel as we could take on board, whilst losing a lot of time in the process. However, it also meant that we would have to watch how much fuel we used for the rest of the trip.

fuel as we could take on board, whilst losing a lot of time in the process. However, it also meant that we would have to watch how much fuel we used for the rest of the trip.

Sunday 16.01.22

One week at sea, already the longest time we had spent on the water without a break. The weather was getting hotter and we still had no wind. As we were not moving very fast Andy and I decided to go for a refreshing mid Atlantic swim. (Another item off the bucket list!)

At this stage we were 1000 miles from Las Palmas and had at least 2000 miles to go to St Lucia, so there was not much chance of a lifeguard being around in case of trouble. We had only been in the water for a few minutes when a Portuguese man-of-war jelly fish floated nearby. Knowing that Private 4000m deep swimming pool they had very long stinging tentacles we decided to get out of the water until it had passed and then it was back in again for a good couple of circuits around the boat.

they had very long stinging tentacles we decided to get out of the water until it had passed and then it was back in again for a good couple of circuits around the boat.

Once back on board I was curious to know how deep the ocean was at this point. The sea chart said 4000, which I took to be feet. Then I looked at the legend and it said 'All depths in metres'. No wonder I couldn't touch the bottom! That evening, for 'sundowners', we opened a small bottle of champagne to celebrate our first week at sea, followed by a tot of rum. This was something that we repeated every Sunday evening.

The following day we continued to sail south at a sedate 2 knots in the hope of picking up the elusive trade winds. We calculated that we were already a full day behind maintaining our five knot schedule and things didn't look like they would improve any time soon.

Tuesday 18.01.22

It was now starting to get a lot warmer and we needed the wind to help keep us cool as well as to make progress. Finally, by late afternoon we had a four hour spell of wind and were able to make 4 knots speed. We worked out that at this point we had done approximately 3500 miles since leaving Hull.

19.01.22

A Bad Day for the Fleet – The daily 'Sitrep' (situation report) via email from Race Control told of a list of disasters and problems that had happened over the last 24 hours, mainly to the boats that had ventured further north and into rougher seas.

One boat, 'Brainstorm', had lost its rudder and was taking on water to such an extent that it was decided to abandon it. As a result of a 'mayday' call, two yachts from the flotilla went to the rescue, each taking two members of Brainstorm's crew and as much equipment, supplies, water and fuel as could be salvaged.

Brainstorm is an X Yacht X-49, which valued at around £630K is not something that is readily available to replace at your local Aldi! (NB – 10 days later we received a report that a salvage tug had been sent out from Las Palmas to recover the yacht, towing it back after fixing a new rudder and repairing the water leak.

This was probably a lot cheaper for the insurance company than having to pay out for a new yacht!) The thought did cross our minds that this would be an ideal salvage at sea situation, where whoever salvaged the boat is entitled to keep it. Unfortunately Brainstorm was over 300 miles away from us and could well have sunk before we got there. So reluctantly, as far as Phil was concerned, we decided to forego that idea!

Also on the Sitrep was news that another boat had one of its cabin windows stove in by a large wave which flooded their saloon, whilst another boat's engine had packed up, meaning that they were at the mercy of the winds and had nothing other than solar panels (not very efficient) to charge their batteries which provided power for their navigation instruments, lighting and radios. And a further boat had had a total electrical failure. So, all in all, it was not a very good 24 hours for some of the fleet. It also highlighted how different the sea conditions were for those who chose to take a more northerly route.

Meanwhile, back on Freeway, we finally had a good day's sailing and managed to clock up 120 nm over the next 24 hours. On the wild life front we had our first sighting of a shark and started to have regular sightings of flying fish, one of which had landed on our boat over night.

I've mentioned how small Freeway was compared to other yachts in the flotilla. That evening we were caught up by a yacht called Caparico II which, according to AIS, was 24 metres long (almost the length of Nantwich swimming pool and more than double our size) sedately steaming along at over 8 knots as we struggled to do just five. Speaking to them over AIS they said that they could motor at 12 knots and sail at over 15 knots! Tongue in cheek, we asked for a tow but they reluctantly declined as they were en route for Antigua, aiming to get there by the weekend. And it wasn't too long before they were out of sight in the darkness and over the horizon.

Thursday 20.01.22

A variable wind meant that we continued to make good progress under sail. However, an increased wind speed also resulted in an increase in swell and we were back to rock and roll. A change in wind direction meant that we had to jibe and in doing so our rudder became stuck adjacent to the stern of the boat and we were unable to steer. In order to fix the problem we had to remove the cockpit floor to enable Phil to release the auto steer mechanism and manipulate the shaft from the helm (steering wheel) to the rudder.

After about an hour the problem was fixed, rudder released and we were on our way again. Whilst this may not appear to be a significant issue the failure of a rudder can present enormous difficulties in being able to steer the boat often resulting in the use of a makeshift rudder on the end of a long pole (if you have the means to make one) and can be very difficult to handle, particularly in rough seas or the use of a drogue off the back of the boat, using the drag in the water to cause the boat to turn (very slowly).

The next day we were surrounded by squalls though none of them were affecting us as we had clear skies overhead. Once again we had a problem with the rudder jamming, but it was cleared quickly. However, Phil ordered that in future the rudder was not to be turned at more than 10 degrees to either side in a bid to avoid further problems. This made turning when tacking or jibing to change direction a much slower and more difficult process.

A small flying fish found on deck

For a further 24 hours we enjoyed good winds and were able to maintain a steady 5 knots. All day we saw flying fish to the left and right of us as we progressed. It is surprising how far they can 'fly' across the waves, using their tails to launch themselves into the air and their pectoral fins to spread like wings, often covering more than 50 or 60 metres at a time skipping from wave to wave.

Watching them reminded me of skimming flat stones across a pond or the sight of tracer rounds being fired as they flashed at speed across the sea.

That evening the weather produced thunder and lightning storms to either side of us, but fortunately too far away to have any immediate effect upon our journey.

Get In Touch

AudlemOnline is powered by our active community.

Please send us your news and views using the button below:

Email: editor@audlem.org